New research funded by the Mississippi IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (Mississippi INBRE) reveals that fish caught from the Lower Mississippi River Basin may contain toxic metals at levels that exceed international safety guidelines, posing potential health risks to consumers.

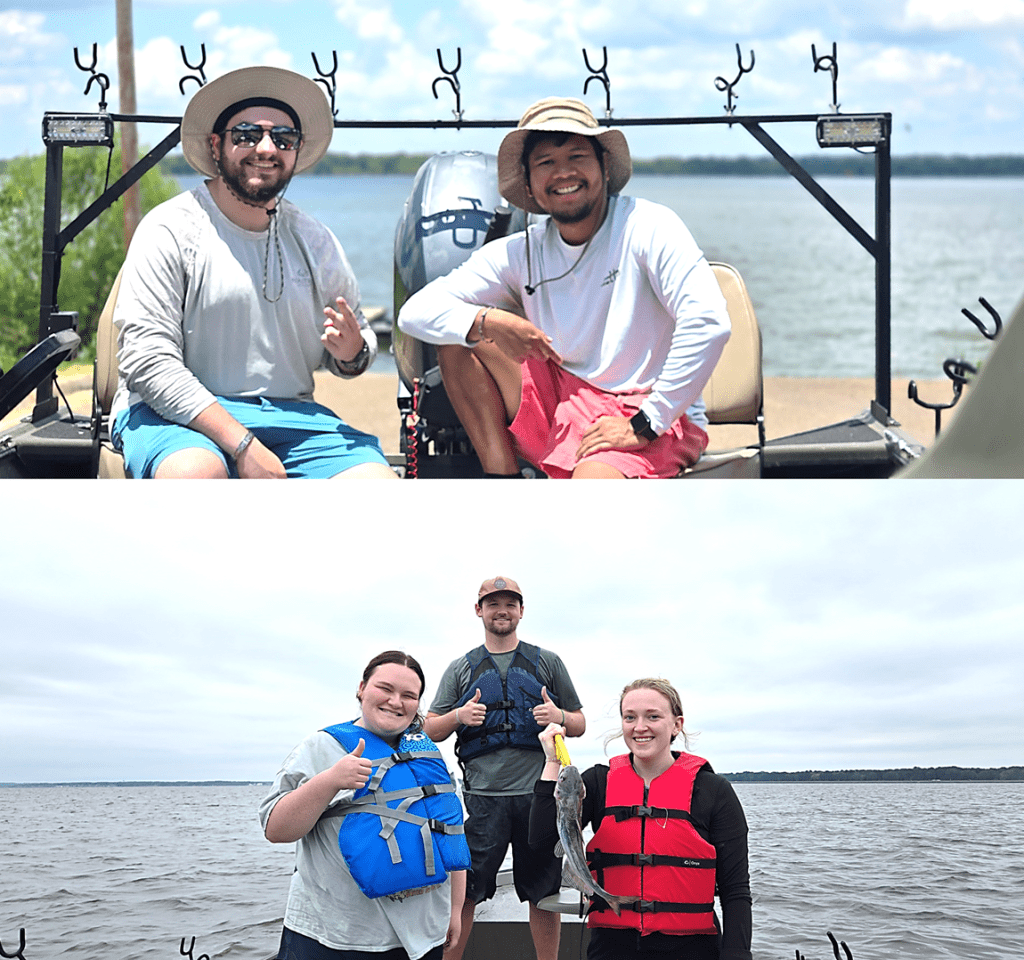

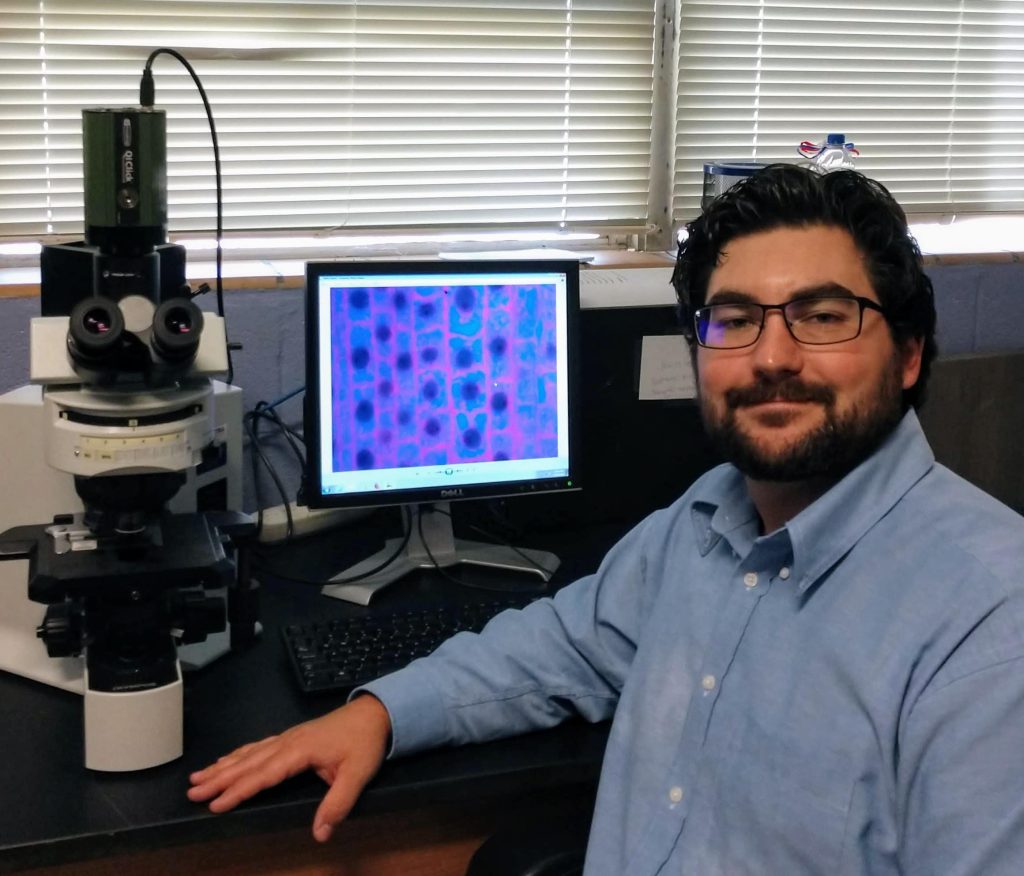

Drs. Scoty Hearst and Trent Selby, professors in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Mississippi College, led the study, which examined fish collected from the Mississippi River in Warren County, Mississippi. The results, published in a recent issue of Elsevier, identified concerning concentrations of toxic metals—most notably mercury and lead—in several commonly caught species.

“Our results indicate that consumption of some fish species, such as gar, from this location should be limited due to unsafe mercury levels,” said Dr. Hearst.

The researchers analyzed a range of fish species, including channel catfish, blue catfish and white crappie—popular catches among Mississippi anglers. Some species were found to contain metal concentrations above safe consumption limits established by the World Health Organization.

The pollution problem extends beyond the river itself. Industrial and agricultural runoff contributes to elevated levels of toxic metals in both water and soil, potentially affecting not only fish, but also food crops grown in the Mississippi Delta.

“The health of the environment directly impacts human health,” Dr. Hearst explained. “Our results warrant further study into these concerns.”

Dr. Hearst’s lab also compared wild-caught fish to farm-raised counterparts, finding that farm-raised fish consistently contained lower mercury levels. He attributes this difference to the ability of farmers to control diet and environmental factors in aquaculture settings—an advantage not possible in natural waters affected by unchecked pollution.

“My team has performed mercury analysis on farm-raised and wild-caught salmon. These results indicated that farm-raised fish were lower in mercury and a safer choice for human consumption,” he noted.

The findings raise critical questions about food safety, public health, and environmental stewardship. Dr. Hearst emphasized the need for expanded monitoring efforts along the Mississippi River and greater public education about the risks of environmental contaminants.

“We need more public outreach and education to warn people of potential hazards in their environment or in their food supply, so that everyday people can make better health choices,” said Dr. Hearst.

Looking ahead, he believes that engaging and training the next generation of biomedical researchers is vital to finding long-term solutions.

“Training students in biomedical research is key for a better future. These young minds create new ideas that lead to scientific innovations, helping to improve healthcare, discover new diseases, and develop treatments for them,” he said.