By: Gary Pettus

Photos By: Jay Ferchaud/ UMMC Communications

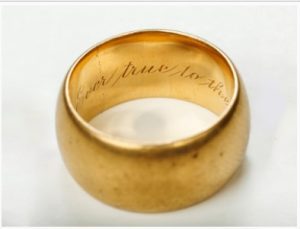

Dr. Jennifer Mack, lead bioarchaeologist for the Asylum Hill Project, displays the gold wedding ring her late husband, Dustin Clarke, discovered. It is inscribed with the words “Ever true to thee.” On a string around her neck is the wooden wedding band that belonged to her husband.

It was Dustin Clarke who found the wedding band with the inscription, “Ever true to thee,” in an unmarked grave.

Clarke, who died last year, was an archaeologist on the Asylum Hill Project, an ongoing commitment to respectfully exhume the remains and memorialize the lives of as many as 7,000 people who were buried on University of Mississippi Medical Center land, the former grounds of the long-vanished Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum.

Clarke is the late husband of Dr. Jennifer Mack, the lead bioarchaeologist for Asylum Hill.

“Dustin was so proud of finding that ring,” Mack said.

Sometime around Valentine’s Day, Mack got a foot tattoo that includes this inscription: “Ever true to thee” – an indelible reminder of a small but telling detail from someone’s personal story, and which has now become part of hers.

“Ever true to thee” is inscribed on this 18-carat gold wedding band, found among some skeletal remains uncovered during exhumations for the Asylum Hill Project.

The 18-carat gold ring Clarke unearthed is one of many personal items collected from the 400-plus graves excavated over the past year-and-a-half from an asylum gravesite on the northeast corner of the campus alongside University Drive. Mack believes the graves date to the early 20th century.

Renamed the State Hospital for the Insane in 1900, the institution served about 30,000 patients between 1855 and 1935, time enough for thousands of residents to die and be buried there – mostly in pine coffins that have not survived. And time enough for their identifying wooden markers to deteriorate and disappear.

A list of asylum patients who were buried in the cemetery between 1912 and 1935 is available; but, without markers, no one knows exactly where each one lies.

The graves have yielded such ephemera as an “At Rest” plaque from a coffin lid; Oxford-style shoes; work boots about three-quarters intact; a coin minted in 1895; railroad tokens; marble footstones; hair combs; gold tooth fillings; and, in more than one grave, dentures tucked under an arm.

But a widely reported discovery is not something a person can wear, buy or inherit. It was an internal organ – a beige, calcified turtle egg-sized object found in December 2022 and known in the medical world as a porcelain gallbladder.

A team of experts, including Mack, reported the discovery this year in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

One of the most remarkable discoveries made on the Asylum Hill Project has been a calcified, or “porcelain” gallbladder. This is an X-ray image of the organ identified by Dr. Ralph Didlake, a retired surgeon and the director of the project.

“It was so much better preserved than the skeletal remains found in that grave,” Mack said. “As a bioarchaeologist, I had no idea that the body could do this or that you could find one preserved. But Dr. Didlake took one look at it and said, ‘that’s a calcified gallbladder.’”

That’s Dr. Ralph Didlake, director of the Asylum Hill Project and UMMC’s Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities; he is also a retired UMMC surgeon.

“It’s one of those things we talk about in surgery training, but never see,” Didlake said. “The list of things it could be is very short. Surgery training is full of ‘zebras’ like this,” he said, referring to the term for a rare or unusual medical condition.

“The porcelain gallbladder is the result of advanced calcification. These days, it would be treated. We have also found evidence of gallbladder removal: Penrose Drains.”

Some of the discoveries, including medical ones, can be identified or their identity confirmed by authorities near at hand. “The Medical Center has access to a lot of expertise and equipment, such as a micro CT scan, that would not be available to many projects,” Didlake said.

“The campus is a huge resource for our understanding of these remains.”

Considering the setting – a mental hospital – and the time – mid-19th century to early 20th century – signs of certain other medical conditions are likely to be come up, Didlake said.

“We should find evidence of tuberculosis; patients were admitted and treated for TB. We would also expect to find bony changes that mark untreated syphilis; patients with the disease were admitted there because syphilis has neuro-psychological implications.

“And we would expect to see evidence of some type of trauma. Patients with head injuries would have been admitted; also, the asylum operated before anti-seizure medications were available, so, we would expect to see trauma from that.

Objects found in Asylum Hill graves include a cap lifter (left, foreground) shaped like a calla lily and used to lift or replace a wooden panel that covered a glass viewing pane set in the coffin lid; and, beside it, a coffin handle. To the right of the coffin handle is a thumbscrew and escutcheon set; these were used to hold the coffin lid closed, as opposed to nailing it down.

“With a closer examination of the remains, we may find such conditions and create what Dr. Mack calls an osteobiography. “One goal of the project is to carefully study the remains of each individual and fill in the stories of these former patients.” Which, in her work as an archaeologist, is the heart of Mack’s motivation.

“I’ve always liked telling stories,” said Mack, who is also an assistant professor in the School of Population Health. “And I enjoy returning people’s personhood to them. When we can do that, we are returning them to their families, too, in a way.”

To that end, a gold ring says more about a person’s soul than a ruined gallbladder. And the souls revealed are not limited just to those of patients. The graves have yielded secrets of many who may have never been buried at the asylum.

Take the two-toned Oxford shoes with inch-high ladies’ heels dating to the 1920s. “No other personal clothing remains were present in this grave,” Mack said. “But these shoes were perhaps important to the patient, or maybe to the people who buried her and who did this for her.”

There is also a story to be recovered, or at least imagined, from several winding sheets (often mistakenly called burial shrouds). “Three or four pins in a sheet is normal,” Mack said, “but there are many more than that in the winding sheets from several graves.”

From this small quirk, she said, “I see a nurse or staff person or even another patient who had this finicky need to have the sheets pinned just right, who wanted it just so. This is not policy; it’s personality.”

Over the years, Mack has had the opportunity to see, through the lens of various idiosyncrasies and intimate mementoes, not ghosts but, instead, human beings – at burial sites across the U.S.

Archaeologists on the Asylum Hill Project recovered this pair of work boots, about three-quarters intact, from one of the graves.

But what sets Asylum Hill apart from the others is its scale, she said.

“As does the amount of involvement from descendants. They continue to help determine the questions we will investigate.”

Around 175 descendants of asylum patients are involved right now, said Lida Gibson, assessment and research coordinator for the project. “The large majority don’t live in Mississippi; in all they represent about 16 different states.”

They are permitted to visit the excavation site and the laboratory where the artifacts are kept, Gibson said. And they are kept abreast of developments through virtual meetings, as well as scheduled public events.

“It’s important to find out what they want,” Mack said. “These are their ancestors.”

In fact, she said, the project now has an official motto: “Ever true to thee.”

“It signifies the Medical Center’s continuing commitment to the patients it inherited: the residents of the asylum.”